The Arrests Of George "Machine Gun" Kelly, Kathryn Kelly, Albert Bates, Harvey Bailey, R. G. Shannon Et Al - The Charles Urschel Kidnapping

Some Introduction:

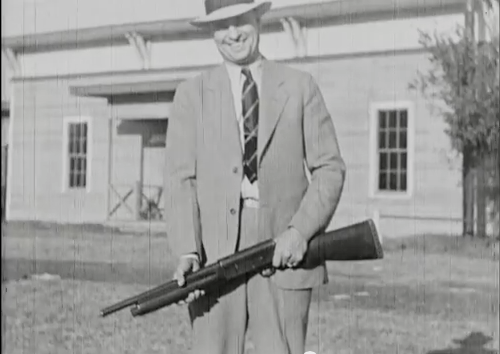

Some of the myth? The regular story of the day in September, 1933. Most press reports examined carried similar stories of Kelly holding a handgun. The official record reveals credible evidence and testimony that Kelly DID NOT hold any weapon at the arrest. No doubt the media embellished on what was said by Sgt. Raney...

The FBI's released Urschel kidnapping file is just short of one hundred volumes long and is massive to say the least. The investigation spanned the involvement of twenty-five or so Bureau field offices and countless members of various local police departments across the U. S. Including the Kellys, over twenty individuals were arrested and prosecuted Federally for various roles in the kidnapping and some later than others.

The involvement of local departments and the cooperation afforded the Bureau are extensively documented in the files. Director Hoover took the opportunity to send local police chiefs in multiple locations letters of commendation on their officers. I note that some original credit at the early stage of the kidnapping belongs to Ft. Worth, Texas detective Edward M. Weatherford and Detective J. W. Swinney. Documents reveal that Weatherford had brought the Shannon's and Kelly's to the attention of the Bureau just prior to, and at the outset of the kidnapping as having possible involvement. Weatherford and Ft. Worth officers also assisted Dallas agents and officers in the raid at the Shannon farm in addition to surrounding investigation. Some officers received monetary rewards from the Bureau for their assistance, and the Ft. Worth detectives above were also rewarded by Urschel.

A post-retirement interview of SA Charles Winstead reveals the names of the Ft. Worth and Dallas officers present during the raid on the Shannon farm. (We've only posted the first page of the Winstead interview to reveal these names)

“We would like to make an accounting of it [Thompson 4907] for the record if anyone knows its location.”

In January, 1934 as promised, Dallas SAC John F. Blake presented Weatherford and Swinney with a Thompson sub-machine gun, serial #4907. This was seized during a raid at the Shannon farm in Paradise, TX. with the assistance of these officers and some from the Dallas PD. The weapon was no doubt the same one purchased at a pawn shop, Wolf and Klar in Ft. Worth, by Kathryn Kelly and used by her husband in the actual abduction. 1959 documents show that the weapon was kept at the Ft. Worth Police Department property room but its whereabouts today are unknown. We would like to make an accounting of it for the record if anyone knows its location. (Confidentiality can be maintained if needed)

Some credit for the actual apprehension of the Kelly's is probably deserving by a twelve-year-old girl named Geralene Arnold. A remarkable young lady, Arnold has long been forgotten in the Kelly saga. She had been "lent" to the Kelly's by her parents as a travel companion but actually acted almost like a GPS system in helping to locate them by sending telegrams to her parents. Ft. Worth detectives assisted the Dallas Bureau in tracing the final telegram sent by Arnold which would lead to the Memphis arrest. The decision of Charles Urschel not to pay her reward money initially caused much consternation within the local community and the Bureau itself, especially from SAC Ralph Colvin.

The involvement of Arnold's father, Luther Arnold, with the Kellys deserves more examination.

One of the unfortunate problems being dealt with is that the FBI file appears to have been released years back when there were strict interpretations of Federal Privacy Laws under the Freedom Of Information Act. This has since changed, but on many documents this release has blackened out the names involved. In some instances, we can accurately assume to whom the name belongs. We're in the midst of checking with the National Archives, where the official file is kept, to determine if better copies are available of selected documents.

We have been able to re-create the identities of some of the personnel involved as a result of the research done by author Bryan Burrough's for his book, "Public Enemies." Additionally, we have been successful in recovering some of the names of the agents involved as a result of the files themselves.

We are also seeking any photos of various local officers involved and copies of any police reports they may have filed at the time.

(This page is under construction as of August/Sept. 2015 and is subject to changes.)

THE "G-MEN" DESCRIPTOR...

While the myth of being arrested holding a handgun prevailed for years, there's also something worth mentioning about the "facts" in "Machine Gun" Kelly supposedly barking those famous words, "Don't Shoot G-Men, Don't Shoot" during his arrest in Memphis, 1933.

Memphis Police Sgt., M. J. Raney shortly after the Memphis arrest of Kelly. Memphis SAC, John Keith reached out for Raney prior to the raid knowing that he was reliable and would work anyplace at anytime.

Birmingham FBI SAC, William Rorer circa 1934. He along with SAC's John Keith and D. M. "Mickey" Ladd with other agents and Memphis police raided Kelly's hideout. The home still exists today. Photo courtesy his son, J. Davis Rorer.

In reality, the term "G-Men" would not have been some "new find" that we're expected to believe. Surely it is not accurate to conclude that it was Kelly (or his wife) who "coined the term."

Use of the "G-Men" expression is easily found through random early newspapers and it's known that it was used earlier than 1933 as really a "catch all" for U. S. government men. In a copy of the prior year's 1932 "Lincoln Journal"we see a crime related article stating in part, "G-Men in underworld parlance means government men." In another instance we found, "G-Men" used in an article about agents of the Department of Agriculture. Merriam-Webster's Dictionary mentions that "G-Man" was first used in America in 1928.

Some might argue that because the term wasn't new, even if Kelly said it, "So what?" The answer to that no doubt lies in the extensive publicity it generated for the FBI exclusive from other Federal agencies.

Over the decades, authors such as Don Whitehead in "The FBI Story," Curt Gentry in "J. Edgar Hoover: The Man And The Secrets," and Bryan Burrough in "Public Enemies,"along with others have written that Kelly's words, above, was the first time Bureau special agents had heard the term "G-men." "Various newspaper columnists and radio commentators—including the dean of both, Walter Winchell—soon picked up and popularized the expression." (This according to Gentry who cites Whitehead's book on Kelly's statement.)

Gentry continues, "A year later, in late 1934, Hollywood adopted a self-imposed movie-censorship code, which banned the immensely popular gangster films. By making the G-man their hero, however, producers were able to circumvent the ban. In 1935 alone, there were sixty-five such movies, the most memorable being G-Man, starring James Cagney."

We did not conduct any type of massive search to document the amount of times the "G-Men/Man" was used in the news media circles prior to 1933, but it's there and it's extremely hard to believe that "it was the first time special agents had heard the term." It's worth noting that at a minimum, SAC Rorer and many of Director Hoover's hierarchy had been in the Bureau since 1924, or earlier. Surely between the term's first use in 1928 and the Kelly arrest in 1933, Bureau personnel must have at least seen those words in the news or were familiar with them from underworld investigations.

Some familiar with FBI history agree that in all probability, Kelly did not utter those famous G-Men words. Yet everyone knows that they took on mythical proportions, becoming synonymous with the FBI.

Actually, in all likelihood, the closest SAC Rorer got to the term "G-Men" was from Kathryn Kelly and found in Burrough's "Public Enemies" research. He states, "In a single, long-forgotten telephone interview Agent Rorer gave to a Chicago American reporter hours after Kelly’s capture, Rorer said it was Kathryn who uttered the historic words. As Rorer told the American reporter, at the moment she was arrested, “Kelly’s wife cried like a baby. She put her arms around [Kelly] and said: ‘Honey, I guess it’s all up for us. The ‘g’ men won’t ever give us a break. I’ve been living in dread of this.’

The logical question here is, if Kelly uttered those famous words, why didn't Rorer mention it in his statement to the Chicago American reporter?

During our review of the FBI files, we did not uncover any reports from SAC Rorer (or anyone else, including other SACs) that Kelly blurted those famous words, ..."Don't Shoot G-Men..."

A copy of Rorer's testimony in the Urschel file reveals no mention of Kelly's words during his trial testimony, nor the words of Kathryn. Lastly, I found no documents such as internal memos to Director Hoover surrounding the arrest indicative that anyone in the FBI thought these famous words were of some earth startling new revelation.

(click to enlarge) Nathan's memo pondering the use of the G-Man appellation...

There was one document dated 1935 which was a memorandum done by Hoover assistant, Harold Nathan to AD Hugh Clegg. It's shown here and no doubt is the result of officials seeing a story published regarding gangster, John Paul Chase. One can readily see that Nathan ponders the use by the media of the "appellation G-Men" as linked exclusively to the Bureau as late as 1935. Of course by 1935, the G-Man descriptor was at full speed with regard to the Bureau.

It might be of interest here to mention that in the 1935 publication of his book, "American Agent," former SAC Melvin Purvis made no mention of Kelly's words or the term "G-Men" in the chapter covering the Urschel kidnapping and Kelly's arrest. Granted, Purvis wasn't present at the arrest however in writing his book, one might think that the subject matter would have been good content to add. Purvis was no doubt familiar with those involved in the Kelly arrest just three years prior and at a minimum, could have obtained supportive statements from them; especially from SAC Rorer. Even if he chose not to mention their names in the book he could have addressed the issue if it was that important in the historical sequence of the FBI's history.

Finally, the FBI's website (no doubt written from research conducted by the FBI's Historian) states, "Some early press reports said that a tired, perhaps hung-over Kelly stumbled out of his bed mumbling something like 'I was expecting you. ' Another version of the event held that Kelly emerged from his room, hands-up, crying 'Don’t Shoot G-Men, Don’t Shoot. ' Either way, Kelly was arrested without violence. The rest is history. The more colorful version sparked the popular imagination and 'G-Man' became synonymous with the special agents of J. Edgar Hoover’s Federal Bureau of Investigation."

KEY NOTES OF THE INVESTIGATION & ARRESTS:

The Urschel investigation, resulting leads and the 1933 arrest of Kelly and confederates, was handled by a multitude of offices around the country. Back at Bureau Headquarters, the case was overseen and directed by SA Supervisor, Samuel Cowley, and others. Most of the major cases of the period were. Within a year's time, "Inspector" Cowley was sent to Chicago to oversee the Dillinger and other major investigations direct at the field level. About seven months later in 1934, he and SA Herman Hollis would be killed in a gun battle with "Baby Face" Nelson and John Paul Chase.

Along with their local police counterparts, the major part of the Urschel investigation lay in the jurisdictions of several of the long time, and some legendary, Special Agents In Charge (SAC). Included were SAC Ralph Colvin of Oklahoma City where the kidnapping occurred, SAC J. F. Blake of Dallas, SAC and former Texas Ranger Gus Jones of San Antonio, SAC Rorer of Birmingham, SAC John Keith of Memphis, the SAC at Denver, Colorado and SAC D. M. "Mickey" Ladd of St. Louis. SAC Jones was appointed by Director Hoover to lead the investigation.

We have seen the legendary SA James "Doc" White appear during the investigation and later at the Kelly's prosecution. It was he who was smacked in the face by Kathryn and who also hit Kelly himself on the head with the butt of his handgun during an altercation outside the courtroom. In the document below, Director Hoover advises the Attorney General of the incident. (SA White, of course, is known from FBI documents to have been the killer of gangster, Russell Gibson, during a shootout attempting to arrest Gibson.)

During preliminary examinations of FBI files on the Urschel case, perhaps the best writing I found of what actually happened with the kidnapping itself is SAC Ralph Colvin's report. It is contemporaneous with the time period and written while the memory is still fresh although Colvin admittedly states he may have mistaken a date or two.

Secondary research from Burrough's book reveals the agent who went undercover to the Shannon farm was SA Tom Dowd. Another agent, E. J. Dowd was also involved in aspects of the investigation. Weatherford also was working closely with SA Kelly Deaderick and both conducted a significant interview with a telephone operator near the farm after Urschel was released. It would be SA Kenneth McIntire who would write a report later explaining the Weatherford's early information. The legendary, SA Charles Winstead was present during the raid at the Shannon farm since Winstead was assigned to the Dallas office at the time.

The Bureau's Laboratory was only a year old at the time of the kidnapping and once again, Special Agent Charles Appel would be called upon to perform the forensic exams needed by the young crime fighting organization.

In an interesting take on Kathryn Kelly, SAC Gus Jones offers an analysis of her revealing a far more dangerous woman than most thought at the time. Jones' report is here.

(Click to enlarge) Inspector Cowley's official report: Dispelling the myth that Kelly held a weapon at the time of his arrest.

Short of reading someone else's interpretation of Kelly's arrest, the "best evidence" is to examine the official record firsthand.

In this regard, a 1936 memo done by Assistant Director Al Rosen lays out what had been previously shown in file but is best for its correction of earlier reports involving placing handcuffs on Kelly. While the names have been blackened out during the FOIA processing of the file, there's no doubt that at least the "Sergeant" mentioned is M. J. Raney of the Memphis Police Department. Rosen's memo, as seen, makes no mention of the supposed famous words uttered by Kelly at the time of arrest.

A second memo prepared by an unidentified special agent shortly after the arrest reveals the confusion of the scene which is totally normal in many arrest scenarios.

The fact that Kelly was not holding a weapon at the time of the arrest, that it laid or was put down by him on a sewing table prior to his arrest, is substantiated also by his own statement in file and is supported by observations of arresting officers.

Oklahoma, where the kidnapping occurred that day, was a haven for many an outlaw. The Bureau field office was commanded by veteran Special Agent In Charge (SAC) Ralph Colvin (see his bio) who, along with others such as Jones, were widely known for getting the job done.

Colvin was a "no bullshit" leader among his men and he was known, as shown in files, for writing some pretty candid letters to Director Hoover. Like others of the era, he was an "old salt" already by 1933 and had the Director's ear on many important matters of the day. After the Kansas City Massacre of 1933, it was Colvin who fired off a letter to Hoover virtually demanding better weapons for his agents. Sometimes comical, his letters to Hoover contain apologies at times for his poor attempts to master the typewriter when no secretaries were available.

With regard to the reward money being handed out by Charles Urschel after his release, once again we see Colvin sitting down at the typewriter and banging out another letter to Hoover, this revealing his disgust at Urschel. Colvin believed the young lady long forgotten in all this, eleven or twelve year old Geralene Arnold, should receive some monetary reward for her assistance and he was adamant that the Bureau not try to claim unrealistic credit, as indicated by the desires of victim, Charles Urschel. Colvin's letter and the possibility of an Arnold lawsuit is here from files. Geralene Arnold's statement to special agents is found here. Secondary research reveals she eventually did receive a partial reward, but further inquiry into this is needed. Over the decades, Arnold disappeared into obscurity. Whether it be from the lawsuit or change of heart, there is some existing secondary research showing that Arnold was eventually rewarded by Urschel.