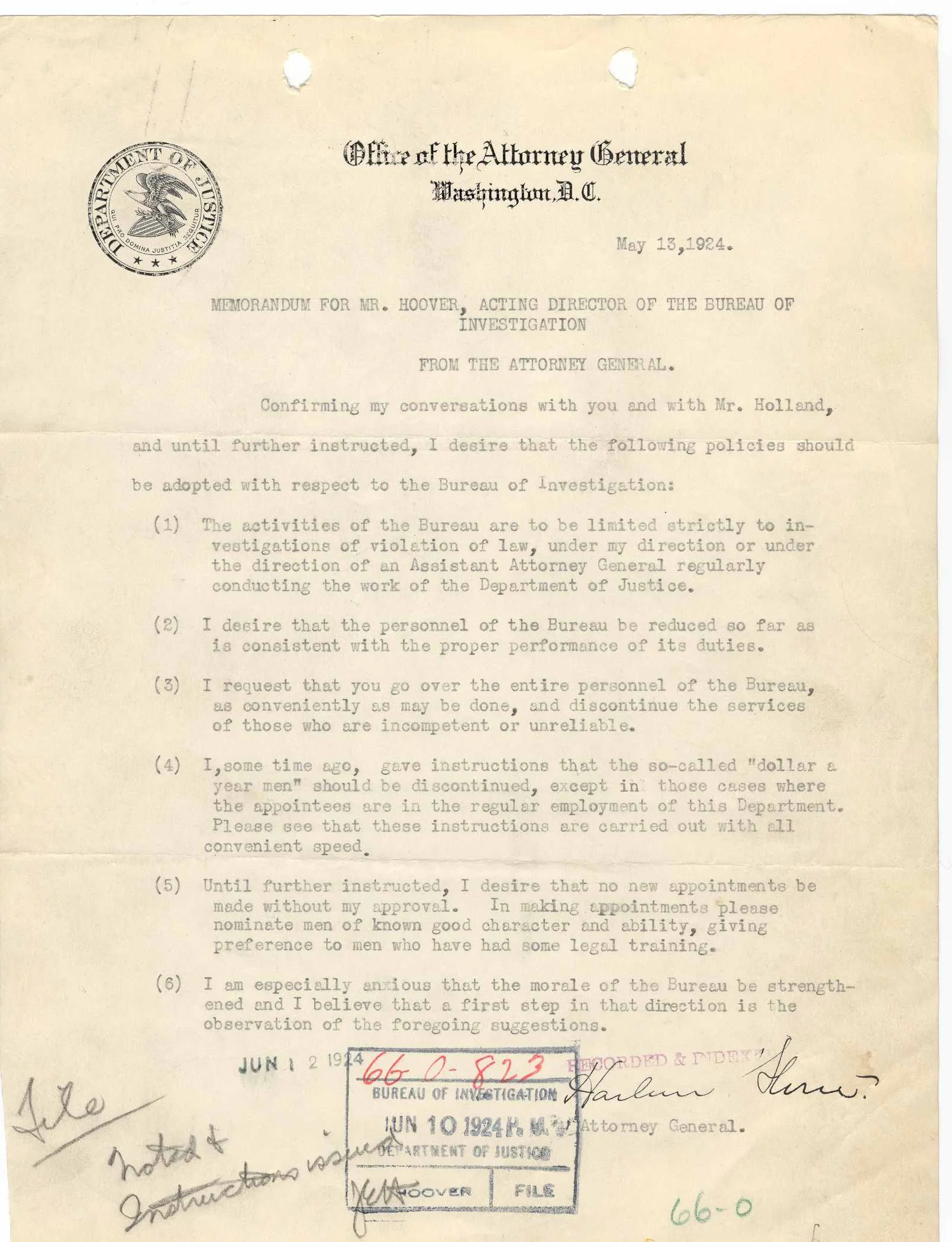

From FBI files: An original copy of the agreement between incoming Director Hoover and Attorney General, Harlan Stone 1924. Hoover's initials "JEH" and his inscription on issuing instructions to his underlings is shown.

J. Edgar Hoover trusted Harlan Stone, and Stone trusted Hoover. While there are no transcripts of their 1924 meeting, it's agreed by most that Hoover made it clear he would not entertain the political cess pool that existed at the time and that changes in the Bureau were long overdue. The above memorandum by Stone reflects a summation of instructions with which Hoover should proceed.

The Teapot Dome Scandal of the early 1900s would claim the reputations of many who surrounded a young J. Edgar Hoover, including his predecessor, William Burns. For the Bureau Of Investigation (BI, BOI) in general, the times were turbulent to say the least. Author, Bryan Burrough in "Public Enemies" describes the beginnings on pages 64-65 and generally accepted:

"The day he was promoted to clean up the Bureau in 1924, Hoover was a stoic twenty-nine-year- old government attorney who still lived with his adoring mother in the house where he was raised, a two-story stucco building at 413 Seward Square in Washington‟s Capitol Hill neighborhood. He was a boyhood stutterer who overcame his disability by teaching himself to speak rapidly, in staccato bursts so fast that more than one stenographer was unable to keep up."

"The Bureau had a sordid history. Created in 1908 to investigate antitrust cases, it had devolved over the ensuing fifteen years into a nest of nepotism and corruption. By the early 1920s, its agents, scattered across fifty domestic offices, were hired mostly as favors to politicians. Its most notorious employee, a con man named Gaston Means, earned his money blackmailing congressmen, selling liquor licenses to bootleggers, and auctioning presidential pardons. In the wake of a mid-1920s Congressional investigation, the Bureau acquired the nickname “The Department of Easy Virtue.”

“In a matter of weeks Hoover cleared out the deadwood, stopped patronage hiring, and instituted a meritocracy.”

"A Senate probe of the Bureau in 1924 led to the resignations and indictments of the BI chief and the attorney general. The new attorney general, Harlan Fiske Stone, was at a loss about what to do with the Bureau. He scribbled down notes of its problems: “filled with men with bad records . . . many convicted of crimes . . . organization lawless . . . agents engaged in many practices which are brutal and tyrannical in the extreme.”2 Stone had no idea who could reform such an outfit. A friend suggested Hoover. He was young, but he was honest and industrious. Stone asked around, liked what he heard, and on May 10, 1924, summoned Hoover to his office and handed him interim leadership of the Bureau."

"Hoover‟s first priority was transforming his force of field agents (which numbered 339 in 1929). His vision was precise: he wanted young, energetic white men between twenty-five and thirty- five, with law degrees, clean, neat, well spoken, bright, and from solid families—men like himself. He got them. In a matter of weeks Hoover cleared out the deadwood, stopped patronage hiring, and instituted a meritocracy. Applicants were screened on “general intelligence,” “conduct during interview,” and “Personal Appearance,” either “neat,” “flashy,” “poor,” or “untidy.”

According to Hoover biographer, Richard Hack, in Puppet Master... "Within months the number of agents dropped from 441 to 402, and the clerical support staff plummeted from 216 employees to 99. No longer was favoritism shown by hiring friends or associates of congressmen, senators, judges, and cabinet members. And field offices no longer were run as independent organizations, but as satellite operations of the Bureau of Investigation."

Burrough's continues, "Hoover ruled by absolute fiat. His men lived in fear of him. Inspection teams appeared at field offices with no notice, writing up agents who were even one minute tardy for work. Hoover tolerated no sloth, sloppiness, or deviation from the new rules that came pouring into every field office, each commanded by a special agent in charge, known as a SAC. (There were twenty-five in 1929.) The tiniest infraction could cost a man his job; when a Denver SAC offered a visitor a drink, he was fired."

“I want the public to look upon the Bureau of Investigation and the Department of Justice as a group of gentlemen,” Hoover told an audience in 1926. “And if the men here engaged can‟t conduct themselves in office as such, I will dismiss them.”

The new Bureau of Investigation, changed later to the FBI, was about to be launched into history.